Friday March 6 2020 was the last day I went to my former workplace in Cambridge, UK. As we have a child who is especially vulnerable to viral illness, we decided, well before it was ‘en vogue’, to stay at home. We received rather ominous letters about us not being allowed to leave the house at all – shortly followed by more reassuring letters that ‘opening a window was allowed’.

What many hoped would be a brief period of atypical working arrangement soon stretched to something closer to two years, and is sadly far from over. Never before have our daily work habits changed so fundamentally in such a short period of time, and the same is true for scientists. Conferences with thousands of participants became completely virtual. Lectures were commonly characterized by vast, silent plains of black squares. One is perhaps best off assuming the silence reflects a breathlessly listening audience. In the entire first year in my new post at the Donders institute I was only able to work in person a handful of times – the rest meant (re)starting a new lab in a new country from the kitchen table (not to mention buying a new house through videochat from a different country – but that’s another story). Although, unfortunately, the pandemic is far from over, we can certainly take stock of the many and rapid changes, and reflect on some of the lessons learned.

The Bad1

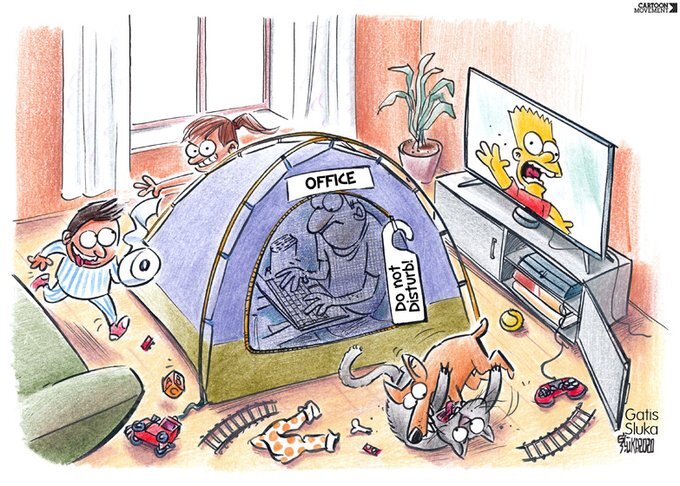

The challenges were, and are, many. For instance, working from home with (young) children is often almost impossible - the combination of acting as a teacher at home and at the same time juggling work responsibilities is, to put it mildly, not ideal. This is especially true for the most exciting parts of our work that demand deep thinking and reflection – Something not particularly compatible with simultaneously assisting in the construction of ambitious cardboard castles, tending to snail collections and home ‘baking’. Of course, the challenges for scientists living alone, especially those away from their home or country of origin, are distinct, but no less challenging.

Scientifically, one of the key drawbacks is the lack of casual, unplanned conversations at the coffee machine. These informal contacts prove not only essential as a ‘social glue’, but also as the origin of many new ideas, contacts and collaborations. As good as Zoom and team meetings have become in terms of the core business of sharing talks and slides, they generally fail at the hard-to-explain intellectual chemistry that arises from serendipitous in-person encounters. This is especially problematic for early career researchers, who build up their social and academic networks through these chance encounters. We try our best to replicate such encounters online, but the best we can do is to approximate them – or to hope to develop new strategies to foster them.

Although the reduction of commuting time entails the clear benefit of ‘more hours in the day’, it comes with other, more psychological challenges. When I drop off my daughter in the morning and am working from home, I can be behind my desk a minute later. This sometimes whiplash inducing switch between parenting and work mode is something that takes time to master. A related challenge exists at the other end of the day – When does working from home turn to living at work? It can be overly tempting to continue working at that same kitchen table during dinner preparation, and/or well into late hours (recent research has shown workdays up to 2 hours longer for those working from home ). For long term maintenance of high level ‘deep work’ it is crucial we find rituals that allow a clear(er) division of work and free time, so that we work from home rather, than live at work, in ways sustainable in the long term. We’ve found some value in the advice and strategies in Cal Newport’s ‘Deep Work’, but many other approaches exist.

The Ugly

Undoubtedly one of the ‘ugliest’ features of this pandemic is that it amplifies pre-existing inequities. Several analyses have demonstrated that the adverse consequences for scientific productivity have been especially pronounced for, among others, working parents, especially mothers, of young children2 and/or people of colour right at a career point where the proverbial pipeline is at its leakiest. As a field, we have to try our very best to consider the differential impact of these challenges at any opportunity we have, to try to adjust for the pronounced pandemic disparities.

The Good

There are, of course, also positive things to come out of our changed work habits. The ability to work remotely and flexibly, requested by people with disabilities of various kinds for decades, turned out to be quite possible once it was needed by a sufficiently large enough group of people. The decrease in commute time means that an efficient day working at home can simultaneously be more productive for work and family/leisure time – a potential win-win. And as challenging as working from home with homeschooling children has been and continues to be, it is also undoubtedly wonderful to be around them (even) more. Personally, I’ve embraced the two most cliched lockdown activities: Learning how to bake sourdough and running further than ever before, both of which are here to stay.

Another benefit is that it has become more commonplace to invite speakers from all over the world to small and large gatherings, bringing greater diversity in backgrounds and topics. Since last year we regularly invite the authors of papers in our journal clubs to join part or all of the conversation, hugely enriching the depth of our reading and understanding.

Hybrid and online working have become almost (but not quite) seamless, and meetings that should be zoom calls often are. I think back with some amazement and no real nostalgia at certain meetings where 20 very busy people would commute to a single location, for only 2-3 central people to speak the entire time. Similarly, the realisation that the cost in terms of CO2 and time away from loved ones for conferences at the very least means we should substantially decrease the frequency of academic activities that involve long distance travel3. In theory, this will ultimately allow a more diversified set of conferences where you can attend the majority hybrid or online, yet benefit from the very real added value of in person conferences for a subset. An added benefit of the virtual conference format is that the chat Q&A can be a great leveler - I have noticed that conference questions in chat format often come from a more diverse, more early career scientists, and are often all the more insightful, knowledgeable and creative for it.

How we’re trying to make it work

At the Donders institute, we are actively trying to learn from the recent past to improve the present as well as the more distant future. Many research groups and scientists from all backgrounds and seniorities have tried out a vast array of creative solutions – Zoom tea breaks, shut up and write sessions, gathertowns, lab walks and elaborate games, and share what works and what doesn’t. One thing my lab has initiated since the more recent tightening of restrictions has been the early morning scrum/rollcall/huddle4: Very brief (5 minute) meetings where everyone outlines their plans and we get to see everyone’s face on a more regular basis. Not only is it nice to see everyone in 2D, if not in reality, but voicing your plans for the day out loud has a surprisingly large beneficial effect on one’s productivity. Similarly, it took a while for me to be convinced of the benefits of Slack, but now that it has become fully integrated it is the virtual heart of the lab – Quick chats and meetings, a steady stream of interesting papers and resources, and attempts to decipher Dutch customs, including stroopwafel etiquette, in our #undutchables channel has become an indispensable part of the lab. Of course, all of the above is from my narrow and rather specific set of circumstances – I’d love to hear from you about challenges I have overlooked, as well as strategies that have worked well (or failed spectacularly).

The motto of my former Cambridge College (Fitzwilliam College) is ‘The best of the old and the new’. As we navigate our way through ebbing and flowing Covid waves towards a future version of academic work, I can only hope we take this motto to heart. Revive what we miss whenever possible, and embrace the new opportunities that arise.

Author: Rogier Kievit

This blogpost is about the consequences of the pandemic for (academic) work, not the pandemic itself, but of course the single largest consequence of the pandemic is direct: (severe) illness and death for many, heartbreak for family, and exhaustion and burnout for care workers.↩︎

https://www.nap.edu/catalog/26061/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-careers-of-women-in-academic-sciences-engineering-and-medicine & https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03045-w↩︎

Please select your least favourite term.↩︎